With the industry in trouble, Massachusetts growers and environmentalists see opportunity in restoring the land.

AMBROOK RESEARCH – About a decade ago, Jeff Kapell was forced to make a calculation about the cranberry bogs he has owned and farmed in Plymouth, Massachusetts, since 1979. Like so many small growers in the state’s storied cranberry country, Kapell knew he needed to make upgrades in order to rival the rising hubs of cranberry production — Wisconsin, Eastern Canada, even Chile — where newer berry varieties outcompete Massachusetts’ legacy vines.

Making improvements would be costly, however, creating a tough equation in a market where oversupply and rising production costs meant that many farmers weren’t even breaking even.

But Kapell knew he had an attractive asset that could help mitigate his renovation costs. Sandwiched between the 12,400-acre Myles Standish State Forest and another protected forest owned by the town was a 14-acre bog where, he said, “production had fallen way off.”

For more than two centuries, farmers have been cultivating cranberries in Massachusetts, but doing so profitably has become more and more complicated. A flood of berries from other markets has led to dips in prices, while climate change has only added more uncertainty.

To survive, some desperate growers are turning to the state for relief.

Growers like Kapell, who figured that he could take advantage of efforts at the state, federal, and municipal level to compensate farmers for putting land into conservation, restoring it into natural wetlands.

With the advice of a local land trust, in 2020 he applied to the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Wetland Reserve Program, which selected the 50-acre parcel, including 36 acres of uplands (the uncultivated raised area surrounding the bog) for funding. The agency pays a going rate depending on the state — that year in Massachusetts it was about $13,400 per acre — to place the land in conservancy, meaning that it can no longer be cultivated or developed. The NRCS also sets aside funds in escrow to be used for reconstruction of the wetlands.

Last year, the town of Plymouth, which had already been working with Kapell and the state’s Division of Ecological Restoration (DER) on project design and permitting, purchased the land for $175,000 with a commitment to revert the bog “back to naturally occurring wetlands.” Construction is expected to begin later this year.

The area where Kapell farms is ground zero for conservation of cranberry bog land. Three bog restoration projects have been completed in Plymouth, including Tidmarsh Wildlife Sanctuary, which at 481 acres is the Northeast’s largest finished freshwater ecological restoration project and is now open to the public.

Efforts to compensate farmers for retiring cranberry bogs ramped up in the mid-2010s, when the state legislature formed a committee of growers, politicians, and scientists to study ways to save the industry.

“I had been losing money for four or five years in a row.

I had had enough.”

“Cranberry farmers were notifying their legislators that, ‘Hey, we’re really struggling here. We need help. We need options,’” said Alex Hackman, director of ecological restoration at Mass Audubon and former head of the state’s Cranberry Bog Program.

In 2016, the bicentennial of cranberry farming in Massachusetts, the Cranberry Revitalization Task Force laid out in its final report the immense changes needed for the industry’s farmers to survive. To be viable, they concluded, growers needed to increase production by planting newer, more productive varieties of cranberries. And to fund those modernization projects, they needed easy access to loans or grants to invest in their bogs.

Even with such measures, they determined, the state needed to come up with an “exit strategy” for the farmers who were ready to get out. A subsequent study found that 20 percent of currently cultivated cranberry bog acreage in the state is likely to be retired given the aging community of farmers, the realities of the market, and the increasingly disruptive effects of climate change.

“This task force said, ‘If all these farmers are going to retire, we need a way to help them retire,’” Hackman said.

In 2017, the DER created its Cranberry Bog Program dedicated to helping the owners of retired bog land with the arduous process of permitting, project design and “pushing dirt.” It received $10 million from the NRCS in 2020 to “protect and restore over 1,000 acres of retired cranberry farmland” and announced six new wetland conservation projects on top of seven ongoing ones.

David Gould, energy and environment director in Plymouth, said he knows of another three or four current bog owners in the town who are “looking at their possibilities” in terms of retiring portions of their land.

“Cranberry farmers were notifying their legislators that,

‘Hey, we’re really struggling here. We need help. We need options.’”

For the region, where a cranberry farmer wading through their bog is an iconic autumn scene, such a contraction can be hard to stomach. There are still about 13,000 acres of cultivated bog land in the state, the second most of any global region after Wisconsin, but consolidation is occurring in an industry with historically high rates of small farms.

“We don’t always necessarily have the best farmland in southeastern Massachusetts, but farming for cranberries was always a possibility,” Gould said. “It’s one of those things that we grew up seeing being done and I think that history is important. Certainly there are bogs that I hope can remain in agriculture, and then there’s others that have really done significant damage to headwaters and diadromous fish runs and it’s fantastic to see those being acquired and restored.”

Although cranberry bogs may resemble natural wetlands, in many ways they disrupt local environments. Dikes and dams have often been built, affecting runs of fish like herring, and nitrogen runoff can pollute waterways.

Every three to five years, cranberry farmers add several inches of sand to the bogs to improve drainage, suppress pests, and promote growth. Over 100 years or more, those layers of sand add up and need to be dug out for native plant species to take hold again.

Much of the engineering work revolves around hydrology, said William Giuliano, head of the state’s cranberry bog program. Priority sites for the state and environmental groups typically have a natural waterway running through the bogs. The majority of the state’s bogs are in kettle-holes, lowland depressions of peatland formed by retreating glaciers.

“Most of our work deals with reestablishing the correct hydrology. Sometimes we’ll plant but if we get the soil conditions and hydrology right, the plants will usually come back on their own,” said Giuliano.

“We don’t always necessarily have the best farmland in southeastern Massachusetts,

but farming for cranberries was always a possibility.”

When the excavators have left the site and the work is done, Hackman said, “it looks like we set a bomb off.”

“But there are clues that we did this well because we’re seeing standing water, rich dark soil, no barriers to how water is moving. The healing has started and nature just takes over at that point.”

For Erik Hamblin, a carpenter on Cape Cod who farms cranberry bogs as a side job, conservation presented an opportunity. He was approached by a local environmental organization about potentially retiring his bogs so they could be used as wetlands to mitigate nitrogen pollution from nearby septic tanks.

“I had been losing money for four or five years in a row,” he said. “I had had enough.” So Hamblin agreed to sell nearly 47 acres of bogs to the group, which will be part of a 78-acre wetland restoration area. He set aside an acre of bog for himself to plant higher-yield cranberry varieties on and some other land that could be developed as a retirement backup plan.

His bogs have been in production since 1849, and their old varieties only produce about 100 barrels per acre, he said, whereas newer ones “can do 400 to 600.”

“Bigger growers can afford to [modernize] and they basically put the smaller growers out of business,” he said.

While retiring bogs is often seen as part of that process of going out of business, organizations involved in restoring wetlands are attempting to make it as beneficial to growers as possible.

“There are clues that we did this well because we’re seeing standing water,

rich dark soil, no barriers to how water is moving.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently awarded a $4.5 million grant to the state, the cranberry grower’s association, and a slew of environmental organizations to target 2,200 acres of current and former cranberry bog land for restoration. The project focuses on farmland “at risk from future sea level rise and storm surge inundation.” Sixty-seven parcels identified as meeting this threshold are still being actively farmed, while more than 200 others have been abandoned.

One unique facet of the project is the proposed employment of growers in the engineering process. The farmers themselves tend to have the necessary equipment for moving large amounts of sandy earth, and the familiarity with the land. So discussions are underway to create a “wetland restoration guild” for growers with expertise, equipment, and interest who could bid and potentially construct the projects.

“We’re trying to be mindful of the economics of making restoration and conservation able to compete,” Hackman said. “And then maybe we start to get a packet of incentives that can rival some of the other kinds of development.”

For Jeff Kapell, the process of restoring his 50 acres of land to natural wetland has been a frustrating one. Years after getting approval for the conservation easement, he and the town of Plymouth are still waiting for final permitting. Navigating the process with a web of agencies has been arduous, and delays have driven up the cost.

“I would say that the regulatory review for this particular project has been about what a strip mall developer in a wetland would receive. It doesn’t reflect consideration for the fact these projects ought to be encouraged,” Kapell said. “Having learned what’s involved, I wouldn’t do it again.”

It seems that all those involved in wetland restoration are aware of the issues with permitting delays and the need to streamline the regulatory process. Giuliano, the head of the state’s cranberry bog program, said that so far completed projects have averaged more than seven years from start to finish — something that the agency hopes to whittle down, along with costs.

Still, in many ways the funding Kapell received has served its purpose. His remaining bogs have now been upgraded with newer high-yield varieties and the business is on firmer ground.

Now in his 70s, despite ups and downs in the industry he has no regrets about purchasing his bogs more than four decades ago after leaving his job as a high-school science teacher.

“It just appealed to me as a way of life. And that has proven to be absolutely correct,” he said.

James Reddick is a Boston-based journalist with a focus on the environment, science, history, and technology. He is currently an editor at the cybersecurity publication Recorded Future News and a freelance audio producer. He has worked around the world, including in Lebanon and Cambodia, where he was Deputy Managing Editor of The Phnom Penh Post. He got his first taste of writing about food and agriculture in a class with Michael Pollan at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

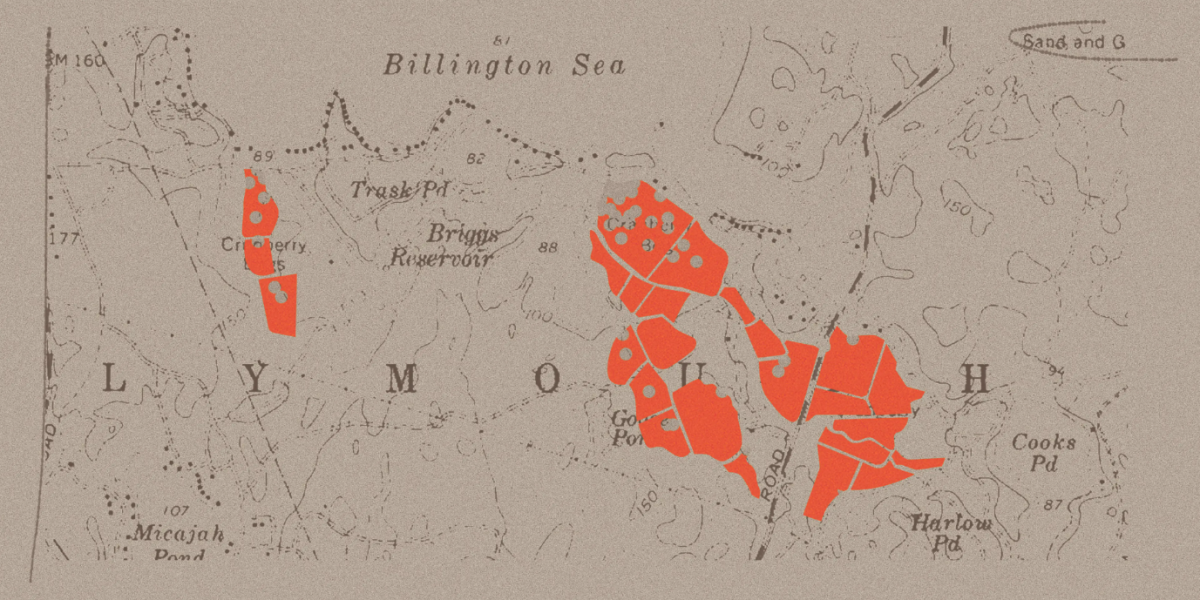

Map Graphic credited to Adam Dixon