THE PATRIOT LEDGER – The coronavirus has left children largely unaffected health-wise, but its impacts will echo through classrooms, band practice and athletic fields as the image of a fall post-COVID-19 is slowly coming into focus.

Schools across the state have already begun the process of laying off teachers and staff to close budget gaps, while also considering the added costs they’ll incur for purchasing protective equipment for staff and students, as per new state guidelines.

Many districts emphasize that they hope to invite the impacted teachers and staff back when their own budget situation is clear, but anticipated state and town budget shortfalls mean this is less likely.

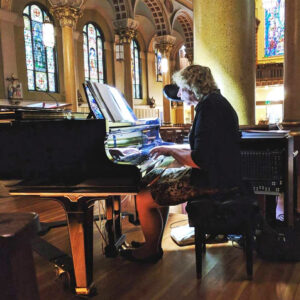

In Randolph, students might have a fall with limited art, music and physical education programs after Superintendent Thea Stovell sent over 30 reduction in force or non-renewal notices to all the art, music and physical education teachers, as well as many social workers and K-8 guidance counselors.

“Districts across the state are facing severe budget reductions based upon predictions of potential reductions to local aid of 10 to 20 percent, and we here in Randolph are not immune,” Stovell said in an official statement.

In Weymouth, 112 educators did not get contract renewals for the fall. In Pembroke, the district is reducing teacher positions by 11.9, and in Hanover, 45 teachers and paraprofessionals were laid off.

In all of these instances, school administrators have cited the pandemic and the uncertainty it has caused for local and state funding as a key factor.

School funding comes from two pools: the state, with its Chapter 70 funding and circuit breaker reimbursements for special education; and local funds, which are set by the municipality’s wealth.

According to the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, two measures of municipal wealth are used: aggregate property values and aggregate personal income, with each given equal weight. The target is recalculated each year based upon the most recent income and property valuations.

The Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation predicts a $6 billion drop in tax revenues for the state due in part to mandated business closures during the pandemic.

At the municipal level, some towns have already confirmed they are unable to meet budget needs.

Weymouth Mayor Robert Hedlund said the school department requested $76.6 million for the next fiscal year, but he projects it will only receive $74.4 million. Other towns are awaiting final numbers with upcoming town meetings.

The Pembroke School Committee anticipates having final local and state Chapter 70 numbers by late July, when the legislature is expected to approve the fiscal year 2021 budget.

“I want people to understand that we’re working in absolute unknown times,” said the committee’s vice chairperson David Boyle during a June 9 virtual budget meeting.

“Look at the mess we’re in with the state and state of affairs,” he said. “There’s no agenda… we’re not trying to hurt anyone, cut a program, or cause any headaches. We’re doing the best we can with the numbers we have… we know it’s a moving situation.”

The cuts in Pembroke include a music teacher, athletic director, guidance counselor, math teacher, and science teacher. Some of the cuts are due to drops in enrollment, which can happen during any year.

Despite layoffs across the state, some districts have managed to keep most, if not all of their staff.

In April, Milton school administrators notified eight paraprofessionals that their reemployment in the fall cannot be guaranteed. However, Glenn Pavlicek, Assistant Superintendent for Business Affairs, confirmed the school has “no plans” for future layoffs or furloughs at this time.

In Scituate, Superintendent Ron Griffin confirmed the school is committed to closing the revenue gap, an estimated $1 million, without cutting any of the district’s 515 teachers and staff.

“We have slogan… we are crew,” he said. “We want to find creative ways to ensure all the crew members that went into the pandemic with us are able to come out to the pandemic with us.”

Griffin said some of these “creative” measures involve furlough days on what would usually be professional development days when students are out of school.

He said school administrators have committed to the same furlough days, in line with the “crew” concept that they’re all in it together and part of the same team.

Despite maintaining all staff for the fall — pending union contract agreements — Griffin acknowledges the hardships all districts are experiencing.

“Like our colleagues around the Commonwealth and country, we’re facing the economic implications of COVID-19,” he said. “We think it’s going to reverberate through fiscal year 2021 and probably 2022.”

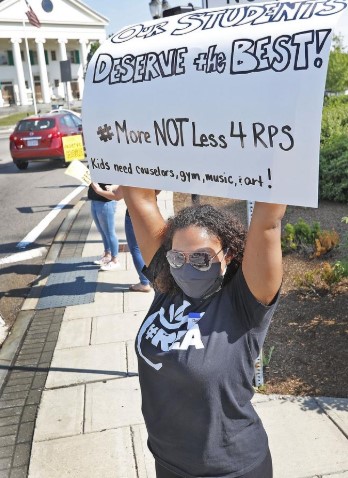

Earlier this month, many educators, students and residents gathered along North Main Street in Randolph to protest the cuts. Their signs were very much a sign of the times.

“More not less” was a common phrase on many posters, but getting more is proving a challenge when it’s anticipated municipal and state budgets will have less to dole out.

“They deserve a chance to compete in the real world. Every child should have physical education every day. Art and music programs have made such a difference in our students,” said Kim Haynes, mother of a 5th grade Randolph student during the rally.

“I’m really upset and really down,” said Sofia Monteiro, a 7th grader at Randolph Community Middle School. “They shouldn’t take it away. It means a lot to a lot of people.”

By Anastasia E. Lennon